Current Temperature

15.0°C

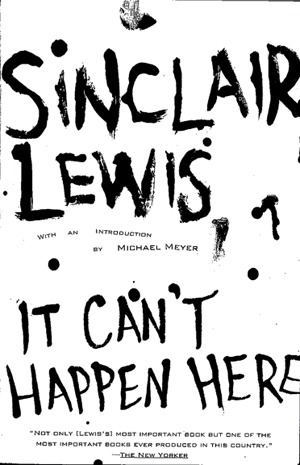

Fascist nightmare depicted by Lewis

Posted on June 17, 2015 by Taber Times Times graphic submitted

Times graphic submittedBy Trevor Busch

Taber Times

tbusch@tabertimes.com

One of the sadder epitaphs for human nature is that many people don’t appear to really value the freedoms they currently enjoy until those freedoms disappear.

There has been a cyclical friction throughout history in many societies between freedoms won and then slowly eroded to a point where populations become resentful of the ruling faction and rise in revolution, or begin the long and tedious process of gaining back what has been lost through working from within their current political and societal structures.

Revolution — for better or for worse — has usually been infinitely more successful than the latter at securing rights and freedoms for oppressed populaces. However, it usually only happens today when a people who are aware of what they might have once had become convinced of what might be — that is the true essence of revolution.

But a successful uprising requires a willingness for self-sacrifice, and the courage to face the monopoly of coercion marshalled by the powers that be, against whatever entrenched form of totalitarianism might hold sway over a given populace. In his classic 1935 novel about the fragility of democracy, It Can’t Happen Here, author Sinclair Lewis depicts a Depression-era America that descends into fascism as it struggles to confront mass unemployment, destitution and economic collapse — and convincingly describing that it very well can happen here.

Following the travails of a small-town Vermont newspaper editor and his family as a president who becomes a dictator, Berzelius Windrip, chillingly seizes power in America, It Can’t Happen Here is equal parts political treatise, black comedy, and horror as Lewis paints a compelling picture of the insidious attraction that fascism can sometimes hold for desperate populations.

It Can’t Happen Here details atrocities perpetrated by Americans against Americans, atrocities that would become commonplace and almost mundane by the conclusion of WWII in 1945. But in 1935, when the novel was published, the true horrors of fascism in Germany, Italy and Japan had yet to be witnessed by then-isolationist America, and yet Lewis is eerily prophetic in his accounts of mass executions, institutionalized racial bigotry and scapegoatism, and the creation of concentration camps for political prisoners.

A prolific author in the 1920s, Sinclair Lewis is perhaps better known today for some of his other popular novels, such as Main Street (1920) and Babbitt (1922), or Arrowsmith (1925), for which Lewis was awarded the Pulitzer Prize. Interestingly, Lewis refused to accept the award at the time, stating that as the prize was meant to go to a novel that celebrated the “wholesomeness” of American life, he couldn’t accept as this was something he claimed his novels never did. Lewis later accepted the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1930, becoming the first American author to receive the prestigious award.

It Can’t Happen Here remains as fresh a warning for modern readers, as it was an awakening to alarming political trends in 1935. Populated throughout with both fictional and non-fictional characters and with a finger placed firmly on the political and social pulse of 1930s America, once would expect the novel to be a dated and boring diversion into how past generations viewed the future, and not much more attractive to a modern readership.

Fortunately nothing could be further from the truth. Lewis’ cogent and persuasive narrative, his searing sense of social commentary, and a hilarious flare for black comedy make It Can’t Happen Here much more than it might appear on the surface, and manages to transform the novel into a timeless warning about the old adage that evil prevails when good men choose to do nothing.

Stylistically, the novel switches back and forth between the face of fascism and its consequences at the grassroots level in Fort Beulah, Vt. and the larger national political scene, where President Windrip and his private army of supporters and thugs, the Minute Men, run roughshod over the institutions of democracy and freedom in America.

If Lewis stumbles anywhere in It Can’t Happen Here, it would be in his description of Windrip’s actual seizure of absolute power following a successful presidential election campaign. Lewis tends to gloss over the actual mechanics of a coup against the Senate and House, but this can be forgiven given the larger context of his purpose, to describe an America prostrated by totalitarianism. That, and his employment of black comedic elements and satire, while often hilarious, can sometimes take away from the more serious message he wished to convey.

It is worth noting that in 1935, fascism still held a rising fascination for many people spanning the entire globe, and would continue to be viewed by a select and powerful few as a ready-made solution to the problems of economic depression. This was all pre-WWII, and it’s easy for us to forget that fascism was once sometimes admired and enthusiastically supported in circles that would surprise most today.

Admittedly, the idea itself still manages to marshall supporters in the 21st century, but most wouldn’t call themselves “fascists”, and sometimes even the “good” ideas many believe they have stumbled across are simply the second coming of the same old goose-stepping cavalry that swept much of the European continent in the 1930s.

One would be remiss to suggest that there is not a certain attractiveness to some fascist ideas, but in most cases they usually speak to the indulgence of the darker side in all of us, dressed up as a celebration of the positive through jingoism, racism, militarism and the propaganda of anti-values. But fascism, despite all its many ills, can instill in populations a deep sense of purpose and belonging that the wayward and easily influenced can find to be a powerful and seductive message. The power of such a message should never be underestimated, even today.

We are all forced to view our past through the eyes of the present, and it is the careful art of the historian to understand the past by juxtaposing himself into the present of our past generations. When reading novels of the past meant to be a prescient warning to the present, most do not age well, tied up in the fears and concerns of lost decades. There are some, however, that remain timeless, and Lewis’ It Can’t Happen Here is one of these rare exceptions.

Exceptionally readable and darkly comical in portraying a fascist nightmare in America, It Can’t Happen Here still manages to convey a message of contemporary hope and vigilance across the eight decades since its first publication.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.